Bjorn the Magnificent

Cat sitting is not something that usually graces anything written about wine, but for me it’s a route to tasting interesting wines.

To explain, my son and his fiancé live in Portobello, Edinburgh, with their wonderful cat Bjorn. On those occasions when they may be away for a weekend I offer my cat sitting services, not for free I might add as attached to my services is a fee, a bottle of wine. The fee is always paid in full, never a basic varietal from the supermarket but always a quality wine with usually with a story to tell. So I was delighted to offer my services to facilitate a recent trip they took to London.

The weekend saw me ensconced with Bjorn, feet up sampling the ‘fee’, a bottle of Georgian Bedoba (ბედობა), Saperavi 2021, all the while wincing as I watched thirty mad men crash into each other while trying to get their hands on a little oval ball.

The Sapaeravi was excellent and so I have included tasting notes below along with some background information about Georgian wine and the qvevri, Georgia’s unique earthenware fermenting vessel.

BEDOBA (ბედობა), Saperavi. 2021

With an average age of 30 years, the Saperavi vines behind Bedoba are planted in the renowned wine region of Kakheti, near the eastern border with Azerbaijan in the Kvareli and Kindzmarauli appellations. The soils here are rich in black shale, and the southern slopes of the Caucasus Mountains provide altitudes of over 400 metres above sea level, bringing fresh acidity and soft tannins.

The final cuvee is a blend of 50% Saperavi matured in stainless-steel, 25% in 5000 litre wooden vats, 18% in second and third 225 litre American oak barrels and 7% Qvevri. After bottling, the wine remained in the cellar for a further 12 months before release.

This wine is a deep dark purple in colour and seems to suggest real depth, the bouquet has pronounced dark fruit aromas with a hint of pepperiness. On the palate the wine was smooth with rich luscious dark fruit flavours followed by surprisingly soft tannins with a slight wood matured hit.

It was very good indeed so I have included a bit of background info for anybody interested along with some links with more detailed information about Georgian wine.

Georgia the cradle of wine ?

Georgia is one of the oldest wine producing regions in the world and while they may not be the only people to think they invented wine they have a better archaeological case than many. Situated as it is at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and the Middle East Georgia enjoys a climate and terrain perfectly suited for the cultivation of grapes.

There is archaeological evidence of vine cultivation and wine making going back over 6,000 years, indeed it is suggested that Georgia supplied wines to the first cities of the Fertile Crescent such as Babylon and Ur.

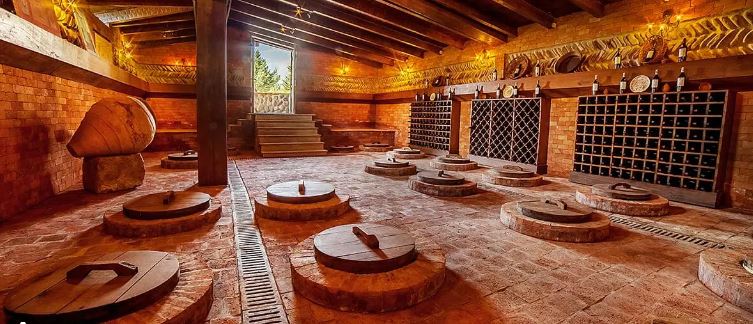

Such a long history has allowed Georgia to develop numerous different Georgian vine varieties, and uniquely they still employ pre-classical methods of winemaking. A Georgian marani or outdoor ‘cellar’ is an area where wine is fermented in qwervi, large earthenware vessels, buried into their brims in the soil.

Everything goes into the qwervi; trodden grape skins, stalks and all. It stays there until needed. The result, whether fermented dry or not, is seriously tannic wine, a taste to acquire, but at its best remarkably good.

As with many traditional wine making methods it’s not suitable to larger scale wine production and is combined with more modern methods to create wines with a Georgian twist. As with the Badeoba Sapervai tasted above, 7% of the final wine was qwervi matured and then blended with wine aged in a combination of wooden vats and stainless steel.

Georgia has three historic wine regions, Kakheti, where more than two thirds of Georgian grapes are grown, is the driest, spanning the easternmost foothills of the Caucasus. Kharti, where qvervi are rare, lies on ground round the capital, Tiblisi. Imereti, to the west has more humid climate.

Modern winemaking came to Georgia with Russian settlers early in the 19th century. Pushkin, the celebrated Russian poet was a fan and preferred Georgian wine to that of Burgundy. However soviet political interference, still active today, resulted in a decline of the main Georgian market to Russia.

Today Georgian wine is slowly becoming more noticed, winemakers are starting to produce wine balanced between the old traditional methodology and more modern techniques. The result, especially from the Saperavi grape, show the best can be complex, full and rewarding with lively tannins, well balanced acidy and exceptionally smooth on the palate.

Qvevri, – ‘Ქვევრი’ – Georgia’s earthenware wine vessels

The qvevri is Georgia’s most important and best-known winemaking vessel, and it remains the centerpiece of traditional winemaking in Georgia

A qvevri (also called a churi in western Georgia) is a large, egg-shaped clay vessel with narrow bottom and a wide mouth at the top. Though researchers believe the earliest qvevri were stored above ground, Georgian winemakers for millennia have buried their qvevri, with only the vessel’s rim visible above the ground. Scholars say the word qvevri comes from kveuri, which means “that which is buried” or “something dug deep in the ground.”

Qvevri are uniquely Georgian vessels, different in shape and function from the clay amphorae used elsewhere. Used for wine fermentation, maturation, and storage, qvevri are among the world’s earliest examples of winemaking technology.

Archeologists date the oldest known winemaking qvevri—discovered in a Neolithic settlement in eastern Georgia in 2015—to 6000 BCE. These vessels are not only important historical artifacts but early evidence of an enduring cultural tradition.

Winemakers using the traditional qvevri method follow the same basic process and principles Georgians developed 8,000 years ago—skins and stems in the vat, natural yeasts, natural tannins.

These are the main steps:

1. Cleaning. The process starts with a clean, well-rinsed qvevri. Traditionally, a worker scoops out the solids at the bottom of an emptied vessel, then climbs inside to scrub the walls.

2. Crushing. After sorting the grapes, the winemaker crushes the bunches in a traditional stone or wooden wine press, called a satsnakheli. The grape must is then loaded into the qvevri, typically with all or part of the marc and stalks, to three-quarters of the vessel’s capacity. The grapes can be either red or white, but the best-known traditional Georgian wines are the amber wines produced in qvevri from white grapes. (Red grapes are typically destemmed at this stage.)

3. Fermentation. Fermentation takes place without intervention, using naturally occurring yeasts and natural (underground) temperature control. Producers typically punch down the cap and stir the vat during fermentation. Fermentation often lasts 3 weeks.

4. Sealing the qvevri. When the cap starts to sink and producers determine fermentation is complete, they seal the qvevri with a lid (stone, glass, or metal) and a clay or silicone sealer.

5. Maturation. Producers leave the solids to macerate in the qvevri for the first three to six months of the wine’s aging before removing them. (This period is shorter with red wines and some white wines.) Producers who want malolactic conversion to take place during fermentation (especially with red wines) sometimes warm the qvevri with a heating element before racking the wine off the lees. The qvevri’s sloped walls allow the yeast and sediment to settle at the bottom while the wine circulates above.

6. Storage. In the spring, when the wine is ready, the winemaker either bottles it or transfers it to another qvevri for short-term storage—since Georgian wine is often consumed before the next harvest—or an extra year of aging.

The history and the central role that wine plays in Georgian heritage is complex, a country that has seen multiple invasions over hundreds of years has retained its own identity and wine making tradition. Further reading, which is recommended, can be found by following these links……

Wines of Georgia or The Georgian wine guild both have further information and a quick online search will find numerous articles on the rise of Georgian wine. I hope as its popularity increases its unique nature doesn’t change too much.

Babylon was a gold cup in the LORD’s hand; she made the whole earth drunk. The nations drank her wine; therefore they have now gone mad. – Jerimiah 51.